You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

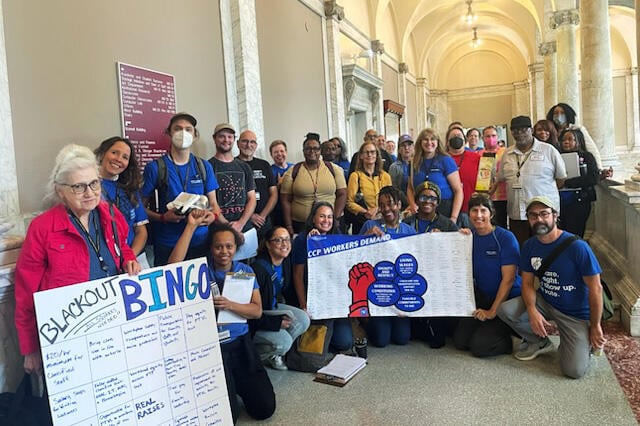

Faculty and staff members are threatening to strike after more than a year of negotiations with the Community College of Philadelphia.

Junior Brainard

The Community College of Philadelphia’s staff and faculty union overwhelmingly voted to allow their bargaining team to call a strike amid prolonged, contentious contract negotiations with the college. But college leaders say they’re working to delay a strike from occurring.

The union, AFT Local 2026, or the Faculty and Staff Federation of Community College of Philadelphia, held a vote between March 10 and 16; 90 percent of the roughly 1,200 faculty and staff members cast ballots, and 97 percent voted to authorize a strike. The outcome doesn’t mean the union has to strike but permits the bargaining team to declare a work stoppage at any moment.

Union leaders say they’ve had at least 30 bargaining sessions over the course of 14 months, with a deal held up by disagreements over their proposed wage raises, staffing increases and subsidized public transportation for employees and students, among other issues. They described employees as underpaid and stretched thin.

“We remain ready and willing to bargain with the college,” said Junior Brainard, co-president of the union. “Our goal is to settle fair contracts without a strike, but our members have shown that the current offer is unacceptable, and they’re willing to do whatever it takes to secure fair pay and better working conditions for themselves and for our students.”

Administrators argue that the college can’t afford to undertake what the union is proposing and that they’ve put forward fair alternatives. They’ve also worked to deter a strike by filing a request with the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board to appoint a fact-finding panel, a neutral third party tasked with reviewing the opposing proposals and recommending a solution. On Tuesday, the college announced the board had appointed such a party to help the two sides reach an agreement. College leaders assert that a strike would now be unlawful until the end of the fact-finding process, when the state-appointed negotiator working for the board makes a recommendation.

Shannon Rooney, vice president for enrollment management and strategic communication at the college, acknowledged that turning to the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board is “a little bit unusual,” though a fact-finding panel has stepped in to handle labor disputes on some other local campuses, including at Harrisburg Area Community College.

“Our concern at this stage in the semester is that a strike would really disrupt our students’ ability to finish classes and graduate on time,” Rooney said. “We believe that by filing for fact finding, not only does it delay any kind of potential strike, it also gives us more time to continue those negotiations.”

She added that college leaders are “very confident” in the fairness of their proposals, so “we feel good about inviting a useful third party into that conversation.”

Brainard called requests to the state labor relations board a “cowardly Hail Mary delay tactic.”

“We need the college to come back to the table and to engage in meaningful negotiations instead of stalling the process with this lengthy procedure,” he said. “We don’t need more facts to be found. We have them. We’ve had them for over a year.”

The Sticking Points

A few key sticking points have held up negotiations.

The administration and the union are particularly divided on wage increases. The union has proposed 9 percent increases in the first two years of the contract and 6 percent increases in the third and fourth years. The college is proposing a 5 percent increase in the first year and 4 percent increases in the second and third year, as well as an increase to minimum hourly wages for classified staff members, starting at $20 an hour in the first year.

Rooney said that under the college’s proposal, CCP classified staff members would be “among the highest-paid employees of their kind in Philadelphia, in higher ed and in other municipal jobs in the city.”

But union leaders believe faculty and staff members would still be underpaid relative to others doing similar work in Philadelphia. For example, adjunct professors at the community college make 25 percent less than adjuncts at Temple University, Brainard said.

The union is open to other offers from the college, like “a one-time adjustment in the first year of the contract to bring us up to what other folks across the city are making,” Brainard said.

The two parties are also at a standstill over whether the college needs more staff. The union is calling for more hires to accommodate a growing student body, while college administrators argue they approved 20 new faculty hires last year and don’t need more.

Enrollment dropped steeply during the pandemic, from 22,166 students to 16,565 between the 2019–20 and 2021–22 fiscal years, according to data from the college. But it’s been on the rise since; enrollment for the 2024–25 fiscal year stands at 17,703.

Brainard said staffing hasn’t caught up to enrollment growth; faculty and staff are down 25 percent since the pandemic, and students are the ones suffering.

“It’s hurting them through overworked and underpaid adjuncts,” he said. “It’s hurting them when they can’t get an advising appointment. It’s hurting them when they’re sitting in overcrowded classrooms. It’s hurting them when there’s nothing more than a skeleton IT crew who can’t fix every broken-down computer, and that’s really why we’re fighting to change the status quo.”

But college administrators argue enrollment fell prior to the pandemic, too, after hitting a peak of 29,094 students in the 2011–12 fiscal year. They say that attrition during the pandemic helped to rightsize the staff without requiring layoffs.

Rooney believes the college is adequately staffed, given that recent “enrollment growth still does not put us anywhere near where we were at our height.”

The union is also pushing for Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, or SEPTA, passes for all students and employees. Its leaders argue that the college has $80 million in reserves and received an additional $5 million from the city council. But college leaders argue they’ve taken these sums into account in their proposals.

“The Federation’s proposals are just simply not affordable, and they would really imperil the college’s future financial position,” Rooney said.

Outside voices have also weighed in on the fraught bargaining process. The City Council of Philadelphia passed a resolution last October in support of the union’s proposals. The union also announced plans for a press conference on Thursday where they’ll be “joined by elected officials from the city and the state, leaders of other major unions in the region, and CCP students who support the faculty and staff’s proposals.”

College leaders are readying themselves for a strike in case it does happen. Administrators are prepared to step in to keep student support services running, though classes would likely be canceled depending on how many faculty members participate in the strike.

William A. Herbert, executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions at Hunter College, said that in general, even the threat of a strike is a powerful tool in these kinds of negotiations. He noted that Community College of Philadelphia faculty and staff authorized a strike in 2019 and won a more favorable contract because of it.

While the vote doesn’t necessarily mean the union will go on strike now or during a fact-finding process, “clearly, if conciliation does not work out, it’s likely there will be strong potential for a strike,” Herbert said. “The strike authorization vote is a very common tactic, and it’s a strong collective statement of resolve.”