You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

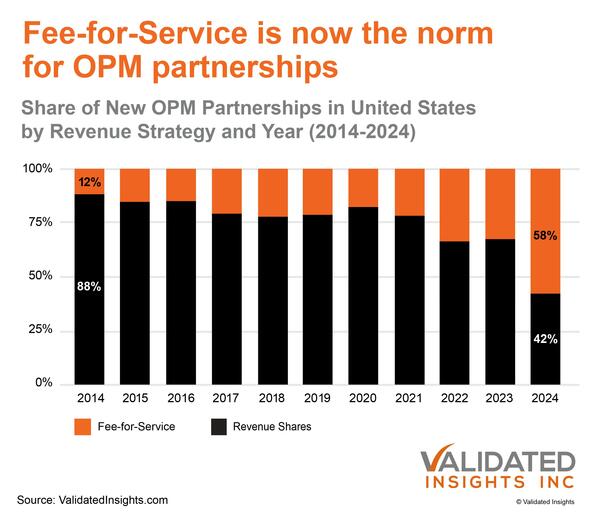

Over the past decade, fee-for-service partnerships between OPMs and colleges grew from 12 percent to 58 percent of all new partnerships.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Course Strat | beekeepx/iStock and SDI Productions/E+/Getty Images | Felix and Rob/rawpixel | cottonbro studio/Pexels

Colleges and universities are relying less and less on outside companies to manage their online programs, according to a quarterly market report from Validated Insights released today.

The new report shows that, for all of 2024, higher education institutions launched just 81 new partnerships with online program managers—the lowest number since 2016.

It also shows that the dominant method for paying online program managers is changing, too. Institutions are increasingly looking for flexibility and customization through a fee-for-service model, which allows them to pay an OPM a set fee for a particular service instead of buying big service bundles and splitting the profits with OPMs.

Industry experts say the rise of fee-for-service arrangements has been a long time coming in a market once dominated by a more controversial revenue-sharing model, which critics have lambasted as predatory arrangements that incentivize servicers to use aggressive, dishonest recruiting tactics to drive up enrollments and maximize tuition revenue.

“For the past 10 years, there’s been a lot of momentum building for the fee-for-service model,” said Brady Colby, Validated Insights’ head of market research. “There was a lot of conversation about how it had a lot of potential for growth, but it was just recently that we saw that come to fruition.”

According to the report, fee-for-service has now surpassed revenue sharing as the dominant business model for OPMs.

Despite an overall decline in OPM partnership activity over the past decade—it dropped 42 percent in 2024 alone—new fee-for-service model partnerships grew from 12 percent to 58 percent of all new OPM partnerships during the same time frame, and 2.2 percent between 2023 and 2024.

Under a revenue-sharing agreement, higher education institutions typically receive a bundle of services from an OPM—examples include marketing, enrollment, retention services and course development—which then gets a set percentage of the overall profit. A fee-for-service arrangement, however, offers services à la carte, and institutions pay the OPM a set fee for each.

Pressure From Regulatory Scrutiny, Pandemic

Numerous factors, including regulatory uncertainty and increasing institutional comfort with online programming, have contributed to the shift away from bundled offerings, according to Colby’s analysis.

“After schools were all forced to move online during the pandemic, they gained a lot of internal functional capabilities that they didn’t previously have,” Colby said. As a result, “that demand for a full suite of services was diminished because these schools were forced to learn a lot of these skills … So, the fee-for-service model, where institutions can largely pick specific felt needs for a partner, continued to grow because institutions got a better understanding of their needs.”

Growing government scrutiny of OPMs—specifically revenue-sharing models that critics argue enable predatory practices—also created “a lot of apprehension around entering into new revenue-sharing agreements,” Colby said, because it’s unknown “if those will be ruled out, terminated or if some other regulatory changes will impact those in the near future.”

The week before former president Joe Biden left office, the Education Department released guidance that said colleges would be held responsible for any “false, misleading, or inaccurate information” that their contractors provide to students. Penalties for such violations could include fines or other sanctions, up to loss of access to federal financial aid.

It’s not clear, however, if the Education Department under President Donald Trump—who has also vowed to dismantle the department—will enforce that guidance or attempt to further regulate OPMs. Phil Hill, an ed-tech market analyst, believes that’s unlikely, and that on the federal level at least, “OPMS are in the clear.”

But he said that doesn’t mean OPM critics are going away altogether: “They’re shifting even stronger into lawsuits and lobbying for state-level changes.” Last May, Minnesota passed the first state law banning revenue-sharing agreements between OPMs and public colleges and universities. In September, a student legal advocacy group sued the University of Maryland Global Campus, arguing that the revenue-sharing model the university has with Coursera violates federal law.

Market ‘Speaking Clearly’?

Regardless of what the future holds for OPM regulations, Hill said he’s somewhat skeptical of Validated Insights’ conclusion that fee-for-service models are now dominating the OPM market.

“It doesn’t mean it’s wrong, but it doesn’t match what we’re seeing,” he told Course Strat. “It’s possible they’re digging up something we’re not seeing in the market, and if so, that’s really valuable.” Hill said that some of the OPMs he’s in regular contact with, including Risepoint and 2U, are “unable to get people to choose fee-for-service.”

Part of the discrepancy, he said, could derive from inconsistent definitions of OPMs. For example, while the report lists ASU Ed Plus (Arizona State University’s in-house digital learning enterprise initiative), Hill said he wouldn’t consider it a traditional OPM.

“Personally, I’d describe an OPM as the primary partner a university is using for an online program,” Hill said. “But that doesn’t mean other people have the same definition.” And without a clear-cut definition or more nuanced analysis, it’s “harder to discern what’s really happening in the market.”

But other industry experts were far from surprised by Validated Insights’ latest analysis showing a shift toward the fee-for-service model.

“The market is speaking clearly,” said Ben Kennedy, founder and CEO of higher ed consulting firm Kennedy & Co. “I don’t think we’re completely done with revenue shares, but we see them so infrequently and I don’t think there are many—if any—of our clients that are actively seeking out revenue-sharing agreements.”

Instead, institutions are increasingly looking for flexibility, and OPMs’ value propositions have evolved as a result.

“Ten years ago, they provided value by providing a whole bunch of working capital and know-how in bringing in new enrollees through massively well-orchestrated digital ad campaigns,” Kennedy said. “But a lot of those competencies are things institutions have since figured out.”

To that end, the OPMs that have endured “are the ones that are willing to offer institutions a customized set of offerings,” in addition to “much more competitive rates than what they were willing to offer 10, 15 years ago when the market was less mature.”